Restaurant Inspiration: Ferran Adrià and the Birth of Food as Art

One of the strongest arguments one could make that food can be art would be Ferran Adrià.

Unless you are among the more obsessively informed foodies, or a culinary-focused world traveler, you could be forgiven for not knowing who Ferran Adrià is. There’s a good chance, though, that you have eaten a dish that owes something to one of Adrià’s revolutionary ideas. Now Adrià has dedicated himself to building a museum and foundation for preserving creativity and artistic endeavor in food.

“Ferran Adrià is the most influential person who has done more for the entire restaurant world than anyone since Escoffier,” says Joe Sparatta, chef/owner at Heritage. When he started training, Sparatta worked at the Ryland Inn in Whitehouse Station, New Jersey, where the head chef had spent a stage working at Adrià’s restaurant, elBulli, before it was widely known.

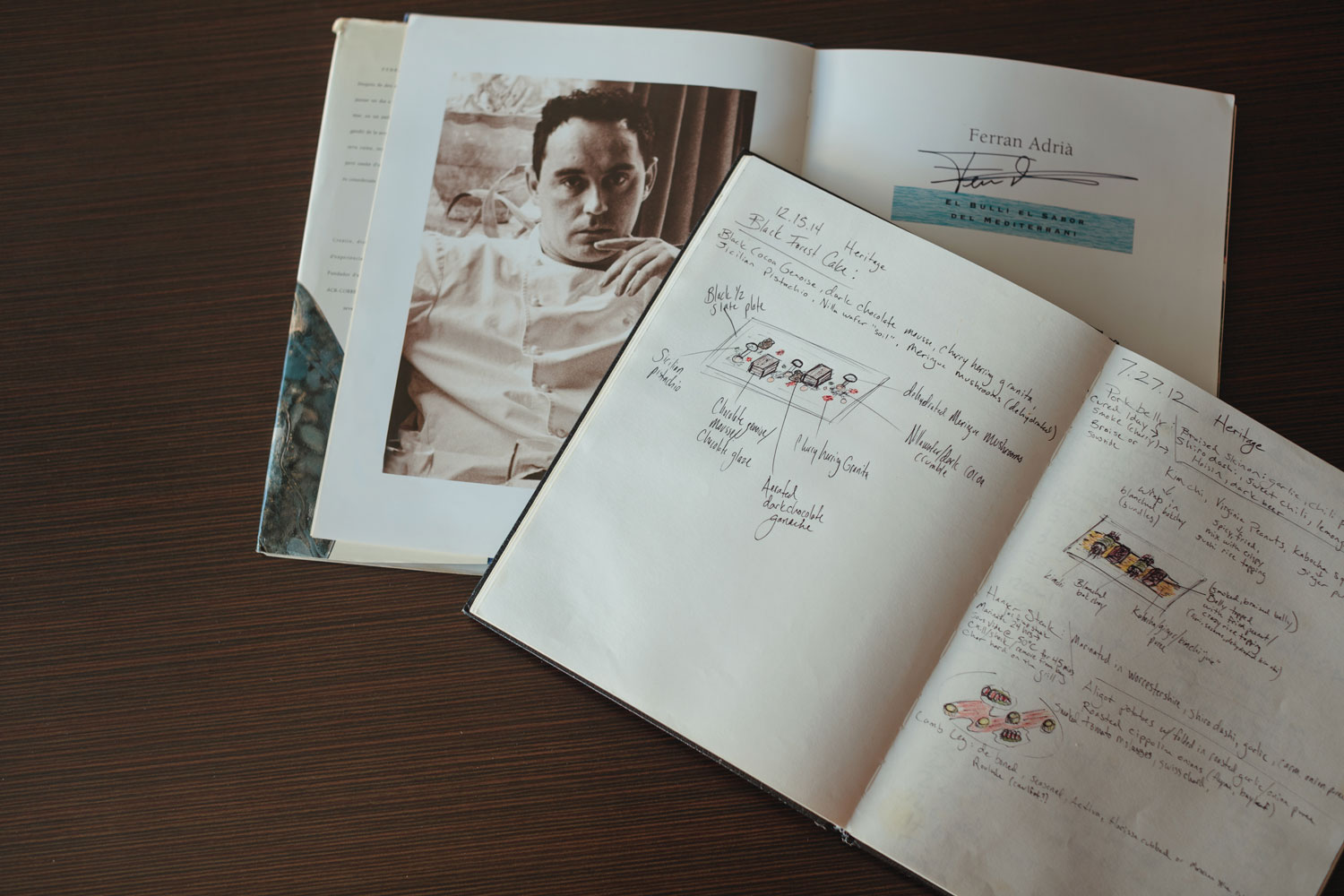

“Working [at the Ryland Inn] was awesome, it was sensory overload,” says Sparatta, who owns all of Adrià’s cookbooks, including a rare Spanish-language edition. “I was very influenced by Adria’s tenacity for documenting your work. It’s freakish how talented and brilliant that whole team was.”

In the late 1980s, Adrià was the co-owner, head chef and creative engine of elBulli on the eastern coast of Spain. Everything about elBulli was remarkable. Diners were served one tasting menu comprised of as many as 30 “courses,” most often single bites. Reservations were regularly sold out years ahead of time. ElBulli won three Michelin stars and, between 2002 and 2009, it was named the world’s best restaurant by Restaurant Magazine a record five times before closing in 2011.

Chefs across the country have been influenced by Adrià’s artistic work either directly, like Sparatta, or more indirectly, like David Shannon, whose award-winning Richmond restaurant L’Opossum is a celebration of art both on and off the plate.

“I once made a lamb dish based on an Alexander McQueen runway show,” Shannon says. “It was inspired by one gown—the colors, the cut and flow of the dress. That has influenced how I plate racks of lamb ever since.”

Like Adrià, Joe Sparatta often draws his plates during recipe development. “For the opening menu at Heritage I drew out every single dish and each component,” he says. “That was a big part of elBulli’s documentation rubbing off on me. My drawing skills are not great, but it helps me think things out.”

Recently, Chef Adrià visited Cleveland to promote his exhibition on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art and discuss the work of his foundation. Adrià and his interpreter spoke with Edible Cleveland editor Jon Benedict.

JB: Did you always want to be a chef?

FA: No. It’s by accident in some ways that I became a chef. To be able to get a visa to go on vacation I got a job washing dishes.

Q: Did you love to eat growing up?

A: In 1980 food in Spain was very different. Almost no one wanted to be chefs or cooks back then. It wasn’t something you aimed for. I just ate like a normal person.

Q: You’ve often been called the greatest chef in the world. So, in your opinion, what makes a good chef a great chef?

A: The important thing is the influence you have. There are people who have influence and people who don’t. In any discipline I value what has influence because then you can measure the impact. Whether it’s better or worse is a different question.

Q: You’ve influenced so many cooks. What influenced you when you started cooking?

A: When someone travels as much as I do, you’re always being influenced. And today with the Internet, in one hour you can have more information than you could have in a month before. That changes the rules of the game.

Q: Your show, “Notes on Creativity,” draws inspiration from several disciplines. Outside of food, what inspires you?

A: Everything. It depends on the moment. What you’re looking for. What you’re not looking for. You could be walking around an airport and get an idea. We all get ideas. The point is whether you bring them to fruition. And whether it has any important consequences or not, whether it has influence.

Q: What surprises you about American food?

A: In 2002, I was one of the first saying that American food was going to be very important, but no one in Europe was thinking it then. It’s logical that the richest country in the world would one day have a very important cuisine. What’s different here is that it wasn’t where an old civilization started. That makes it very different than other places. It’s a mix of civilizations. When you’re in Spain there’s a mix also, but there are certain things that are part of an old civilization. America is defining itself as it goes along, relative to cooking. It’s almost easier to understand contemporary American cooking than it is to understand traditional American cooking.

Q: What advice would you give a home cook?

A: Cook logically. They should do what they can do and not try to do more than that. Simple things. There are lots of wonderful things that are simple. Use the healthy products that are available and ready-made. You don’t have to obsess about making every single component for yourself at home. Within your budget, buy the best-quality products.

Q: Do you have time to cook at home and if so, what do you like to cook?

A: Chefs are always cooking at restaurant kitchens. They are never cooking at home. Cooking at home is to do it every day. Really having to cook at home. One or two days a month perhaps you make something clever, but you’re not usually cooking at home.

Q: Do you ever eat anything bad, like go to McDonald’s?

A: Food on airplanes is sometimes is just as bad as McDonald’s. Not to demonize all of it. Sometimes at the end of the day it depends on everyone’s financial resources and what they have. If you have two McDonald’s hamburgers a month, it’s not a bad thing. Two or three a day is a different situation. But sometimes people don’t have the resources to eat better quality. If an amazing-quality hamburger cost a dollar, everybody would be choosing that. You have to be careful with these topics because you don’t want to fall into condemning populist food. The truth is you can go to a market and get good quality and cook it at home and can afford it.

Q: What is essential to teach children about cooking?

A: They should cook what they can’t buy. There are things that are not that good when you buy them. You can buy a good-quality tomato sauce because there are good ones, but not all industrial food is good because, for some things, technology has not been able to produce a good-quality version of it. A stew, for example. Meat for example, you can buy one prepared in small production, but fish that’s been cooked, that’s hard to get one that is good. It has to be freshly made.

This interview originally ran in Edible Cleveland Issue #12.